The Tragedy of West Oakland

Have you ever seen Exchange Place in Jersey City? Exactly opposite of New York’s Financial District, across the East River, it’s an almost comical sight. It looks like an extension of Manhattan, full of gleaming skyscrapers slammed right up against the water. It’s a busy urban hub, home to Goldman Sachs’ secondary office, a walkable downtown neighbourhood, and a cluster of residential towers squeezed right up against the ferry terminal.

For a certain type of commuter, it’s a dream. Someone living in Exchange Place, the area of Jersey City situated right against the river, has three direct paths into FiDi. A PATH train can take you to World Trade Center in four minutes. If you want to commute without going indoors, a direct ferry runs once every seven minutes from Paulus Hook to Battery Park City. The journey takes only seven minutes, making your worst case travel time about fifteen minutes.

It’s one of the most affordable places that a commuter into lower Manhattan can live. The neighbourhoods around the Financial District – Soho, Tribeca and the West Village – are some of the most expensive in the country, and the specific geography of Manhattan makes accessing the Financial District from cheaper neighbourhoods inconvenient. (On top of that, a neat interstate arbitrage means that Jersey City residents can make New York City salaries and take 3% more home than their colleagues after taxes.)

The PATH’s inconvenient late-night service means it's not perfect for everyone. Young yuppies happily trade off those delicious tax advantages for a decent nightlife. But it’s a wonderful, more-affordable suburb for families with young children or those who want to spend quiet evenings at home. And, importantly, its existence makes housing in other parts of New York cheaper for those who would rather live closer to parties.

If you squint, San Francisco looks like Manhattan: its financial district is right against the water and inaccessible by land. Right across the Bay is a vast expanse of the mainland, connected by train. So when I look across from Embarcadero to the other end of the Bay Bridge, I somewhat expect to see a Jersey City-like built-up area.

But there’s nothing there. And when I take the BART and stop in West Oakland, a little part of me looks out and cries out in despair for what could be. Indeed, why isn’t it a vibrant, metropolitan commuter suburb? And it turns out that that it used to be, but it was killed by the highways. The real mystery, to me, is why it hasn't come back yet.

Why West Oakland?

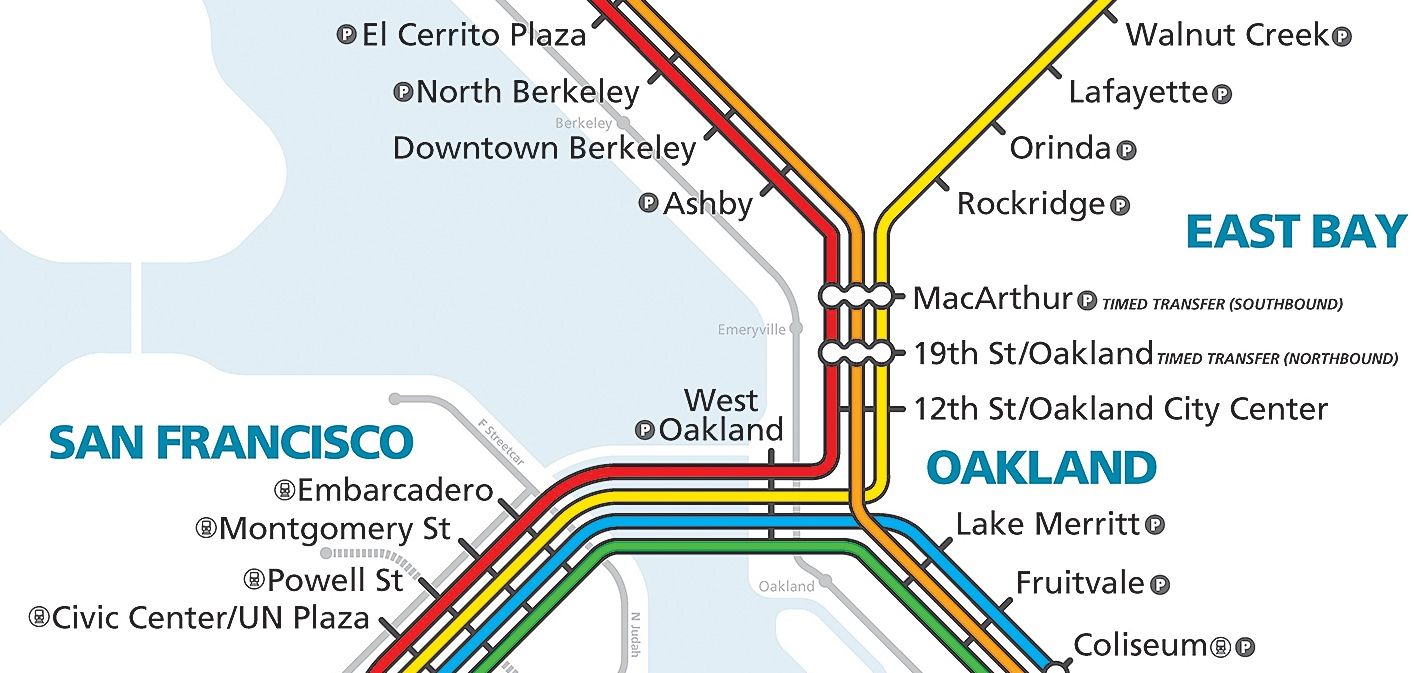

West Oakland has the best BART connectivity in the Bay Area. It is the only stop in Oakland does not require you to run through downtown Oakland to get to San Francisco. Every transbay BART train runs through it.

Compare it to MacArthur, an Oakland area earmarked for development. In the middle of the day on a weekday, there are 8 minutes between trains, and it takes 16 minutes to get to MacArthur, meaning that in the worst case, a MacArthur-to-Embarcadero trip takes 24 minutes.

From West Oakland, trains run every 3-4 minutes to Embarcadero and the trip takes 6-7 minutes, making the worst case travel time 11 minutes. This means a West Oakland to Embarcadero takes 15-to-20-minutes, compared with 30-to-40-minutes from MacArthur, once you factor in time to get in and out of the station on both ends.

(MacArthur is actually not that far from the entrance to the Transbay tunnel, but trains going into San Francisco have to divert and run through downtown Oakland, adding ten minutes to the overall commute. In fact, in 2001, BART proposed building a bypass from the Transbay tunnel to MacArthur, which would improve throughput and commute times throughout northern East Bay. Combined with a second transbay tunnel, it would effectively double BART’s capacity. Obviously, it was never built.)

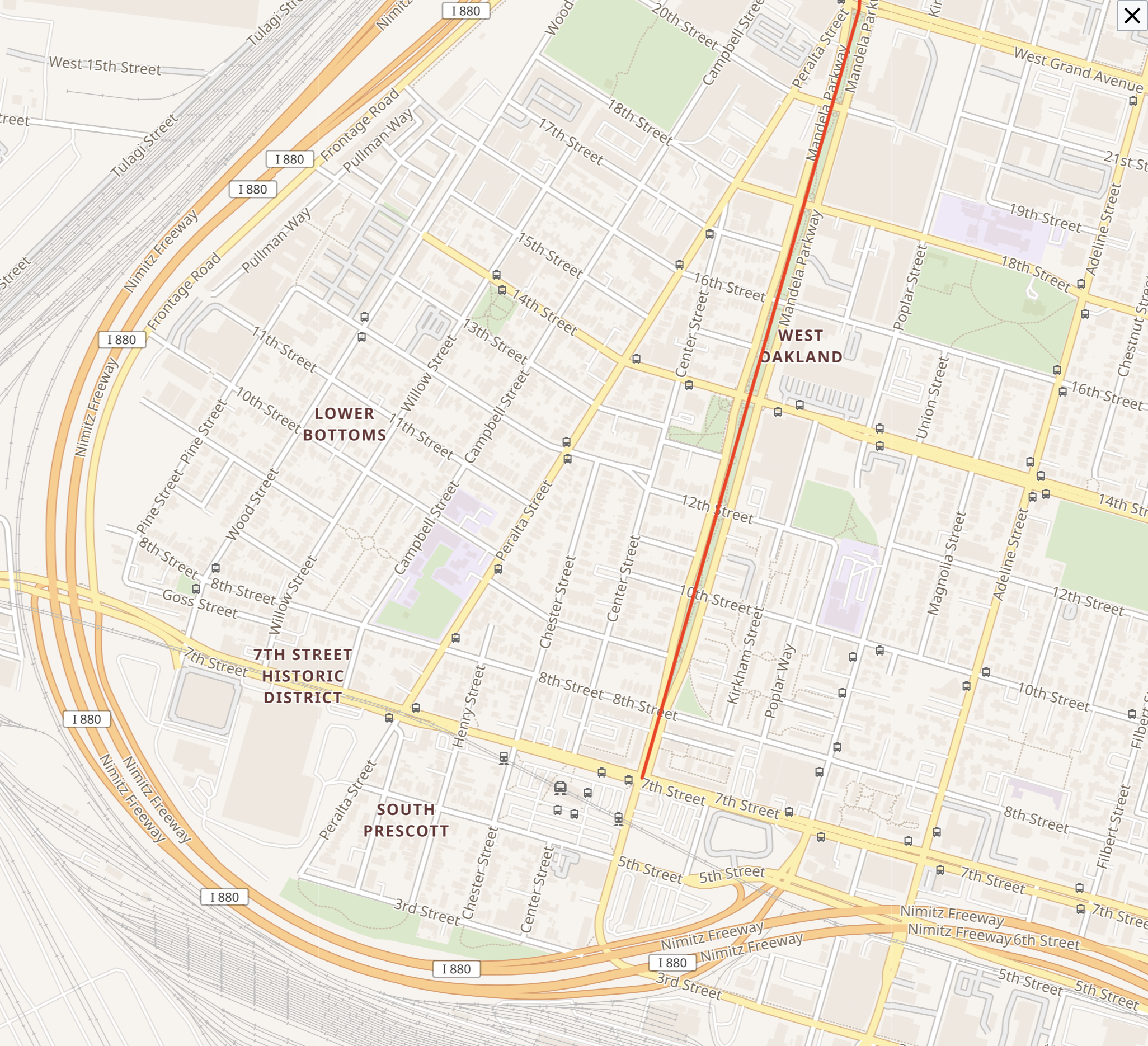

Every East Bay BART commuter passes through West Oakland, every day. All you have to do is look out the window. Immediately outside the station is a block of four-story affordable apartments. But beyond that are empty lots, abandoned stores and blocks upon blocks of single-family houses. There's little commercial activity, and, separately, crime rates are high. The neighborhood's prices reflect it: lots of land right next to the BART station sell for $200k.

It wasn’t always like this. The simple fact of geography that I noticed has made West Oakland a highly desirable area for almost a century. In the 1800s and early 1900s, American rail companies built cross-continental rail. Those lines terminated in West Oakland. This made the area a massive rail hub, and working-class immigrants from Ireland, Greece, and Italy moved to work for the train companies. West Oakland in particular was a company town for Southern Pacific, the dominant railroad company in California.

During World War II, it became a center for shipbuilding efforts on the Pacific Front. Black Americans from the South were drawn to the economic opportunity and moved en masse into the neighborhood. This made it a vibrant place — West Oakland was eventually known as the ‘Blues capital of the West.’ Black-owned businesses filled the streets, and a young shoe-shiner remarked that when he shined shoes, he shined the shoes of Black preachers and lawyers. Seventh Street was its main street, a bustling thoroughfare of butcher’s shops, groceries, and nightclubs.

This documentary provides a lively depiction of life at the time, as told by former residents. Ironically, it's funded by the California Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. It features interviews with porters, with women from the South who moved up to work on ships, with people who used to walk by the neighbourhood stores and people who used to go to the jazz clubs in the area.

What happened? If you’re American, it’s probably obvious. But it often shocks foreigners — like me — how much of America’s current urban landscape was created and not emergent.

A naive observer might think that the low-rise strip malls and dark underpasses that fill America result from humanity trying and failing to fill a mass of land too large for it. In some parts of the country, perhaps. But all too often, those strangely abandoned urban areas were razed and destroyed to make space for automobiles and highways.

That’s what happened to West Oakland. In the 1950s, its prime location made it an attractive target for the Federal Highways Administration. With the mandate of creating easy access from desirable suburbs into cities, it was granted huge powers of eminent domain to take land, tear down the houses on them, and put up suburbs.

In line with policies at the time, those highways tore ‘white roads through black bedrooms.’ West Oakland was a redlined neighbourhood. It was in a geographically ideal area. It had working-class population, with a largely non-white population, that couldn't advocate for itself. It was the perfect target for 'urban renewal'.

And so the FHA put up the Cypress Freeway right through Seventh street, introducing access to the Bay Bridge for suburbs in the north, and tearing the neighbourhood into two.

The neighbourhood limped on until the introduction of a BART station in the 1960s. Former residents describe this as its death knell. I’m not sure it needed to be — Asian cities provide prime examples of how train line access, even those with overground access, can make a neighborhood more and not less desirable.

But some of the choices around BART in the area were baffling. West Oakland station was built as a Park and Ride station, even though almost all neighborhoods around it are also served by BART. As a sign of how little the planners cared about the area they were tearing through, the station was called "Oakland West" for years, instead of "West Oakland".

Planners also put the line overground. This was not a West Oakland-specific problem – the Berkeley BART line also originally ran aboveground, until the neighbourhood gathered together and raised the money to put it underground. It took nontrivial amounts of political organization, too – BART originally tried to claim that it would cost $10m per mile to put the line underground, but Berkeley residents hired their own engineers and argued that it could be done for $5m per mile.

But West Oakland, filled with working-class families, could not put up the political opposition or raise the funds needed to do so. The resulting noise made it impossible to hear music in the neighborhood’s jazz clubs, and residents slowly drifted away.

What about today?

The sixties were a long time ago. Things have changed. For one, California is suffering from a critical housing shortage. American tastes in urban design are trending more towards transit-oriented development, because of concerns about climate change and a wider awareness of how the rest of the world lives.

West Oakland itself has changed, too. In the 1980s, the Lomo Prieta earthquake destroyed the Cypress Freeway. Thanks to local opposition, it was redirected around the neighbourhood instead of through it when it was rebuilt.

If the freeway killed the neighbourhood, why didn’t moving it away bring West Oakland back? Yes, it’s hard to undo the damage from decades downzoning and destruction. But it’s been forty years since the Cypress Freeway fell. In light of the Bay’s housing crisis today, why isn’t West Oakland more built up?

I’m not alone in thinking there’s a missed opportunity here. Mandela Station is a beautiful, utopian vision of a beautiful, walkable neighbourhood that would replace the current BART parking lot. It hasn’t been built because, as far as I can tell, the developers haven’t been able to raise funding – though maybe that's changed recently.

There are other attempts to build in the area. Indeed, the block immediately in front of West Oakland is home to three-storey affordable housing apartments. Developers have been trying to build market-rate housing there for years, like the Golden West project that would add 222 market-rate units and 16 low-income units.

Unlike in most San Francisco suburbs, opposition to building in the neighbourhood isn’t coming from wealthy homeowners. 70-80% of West Oakland residents rent.

Instead, it’s being opposed by a group of labour unions. Developers won't commit to using union labour on the grounds that it would make development unaffordable. They're probably right, but Oakland is a union town, so new buildings will be held hostage until morale improves.

Occasionally, some people say building will gentrify the neighbourhood and destroy its Black neighbourhood character. But as Darrel Owens cogently points out, gentrification doesn't look like new towers. The face of gentrification is East Bay neighbourhoods that look like traditional suburbs and don’t build. Those are the neighbourhoods that end up pushing out their Black and Latinx population:

Let's go north to the MacArthur BART station and see if there’s a pattern.

- West of MacArthur BART: Longfellow District. 2,848 Black residents in 2010. 45 homes built in 10 years or a 1.7% increase in housing.

- East of MacArthur BART: west Temescal, including the MacArthur BART Towers. 975 Black residents in 2010. 580 homes built in 10 years or a 27% increase in housing.

54 Black residents were displaced from the Temescal tract including the MacArthur BART highrise and Longfellow.

1,019.

Yes, read it again: 1,019 Black residents had gone. 35.8% of the Black population of Longfellow disappeared versus 5.5% for the MacArthur tower side. If we looked at that as a weekly average, that means for every 4 days in the last 10 years, 1 Black person disappeared from Longfellow—just one Oakland neighborhood alone.

This is the largest decline of Black residents of any residential neighborhood in the entire East Bay and reveals that Northwest Oakland is ground zero for Black displacement and gentrification in the Bay Area.

So, unfortunately, it looks like a funhouse mirror version of classic NIMBY-ism. There are no entrenched homeowners to fight construction, but a combination of unions plus slow planning bureaucracy and affordable housing requirements bleed all attempts to build to death. And meanwhile neighbourhood residents are denied cheaper rents, commercial opportunities, and all the other benefits of urban development.

West Oakland could be so much more; it could be the Bay's Exchange Place. The tragedy of West Oakland is not merely that it was devastated in the 1950s. It is that modern NIMBY-ism won't let it build itself back up to the vibrant neighbourhood it used to be.