Extreme Residential Lighting

Or, more than you ever wanted to know about consumer LED light bulbs.

Table of Contents

If you’re reading this, you probably spend a lot of time indoors. Apparently, humans spend more than 90% of their time indoors – more than some whales spend underwater! (This is a fact often cited by the indoor air quality movement, but I have temporarily appropriated it for the indoor light quality movement.)

There's nothing wrong with that. The indoors is pretty great. It’s climate-controlled, computer-friendly and comfortable.

Unfortunately, it’s often not bright enough for me.

When I was in university, I spent a lot of time working in rooms like the one above. They're often known as sunrooms or solariums. Over the course of four years, I learned that my ideal room for knowledge work has floor-to-ceiling windows on one side, with a beautiful view onto some green or blue feature of nature.

My adult life is better in many ways, but in this regard has been sorely disappointing. I’ve spent a lot of time working from small, dim apartments and dreary office spaces. Needless to say, neither of these fill me with as much joy as the solariums I worked in during college.

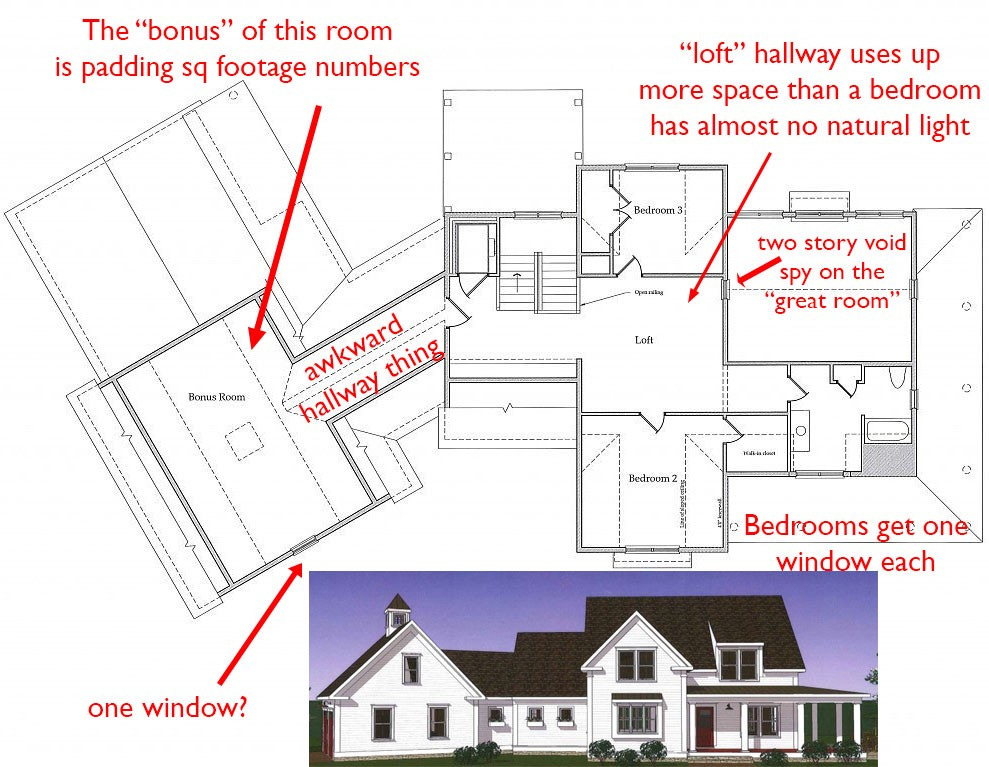

Strangely, I’ve noticed that America in particular seems to have a dearth of light in its newer homes and spaces. (I rarely feel this way in Europe or Asia.) Maybe it's because multi-family apartments are notoriously dark because of their deep floorplates and double-loaded corridors. New York is particularly bad for this, since it’s culturally acceptable for brand-new luxury apartments to rent with no overhead lighting installed in units at all.

But it’s not just the apartments. I have also lived in single-family homes, subject to none of these requirements, which are oddly filled with dark ‘bonus rooms’ and bedrooms with only one tiny window. Simon Sarris critiques this example single-family home beautifully here.

At some point I realized I was fitter, happier and more productive when I had more artificial lighting in my home during the day. Other people on the internet have noticed this too, especially people who live in cold and dark countries, where even in old buildings they just don't get very much light during the winter. (Look up Seasonal Affective Disorder’ for more on why.)

Ideally we would all be lucky enough to live and work in beautiful and well-designed buildings on the equatorial latitudes. But if, like me, you don’t, it turns out that you can use artificial lighting to improve your health, happiness and life. It requires some work, and there are some tricks to it. But if you want to know how I've come to think about it, read on.

(Though before we do that, I want to emphasize that this isn’t the lighting solution to solve all problems. If you want an aesthetic lighting guide, read Simon Sarris’ excellent guide to lighting a home. I recommend the extreme residential lighting approach only for studies and particularly dim living rooms.)

Consider the lumen

One very cool fact about the world is that we know how to assign numbers to brightness. The SI unit for light is the lumen, which roughly is used to measure how much light a source outputs. More relevant for us, however is the unit lux, which is lumens per square meter. In other words, lumens are a measure of emitted light, and lux are a measure of perceived brightness (i.e. what we actually care about).

I don’t have a great intuition for thinking about a single lumen or lux, but you can get a sense for it by considering the lux of common situations:

Scenario Lux Cozy night-time light 30-50 Indoor room 100 Warehouse/industrial space 500-750 Overcast day 1000 Full daylight (not direct sun) 10,000-25,000 Direct sun 32,000-100,000

(source: Wikipedia)

Surely there can’t be that much of a difference, you ask? It’s surprisingly unintuitive, but there is, because apparently we perceive light during the day logarithmically!

This is one of the anecdotal reasons I’ve heard cited for why Season Affective Disorder happens – you actually get orders of magnitude less light during the winter than the summer. (This might also explain why British people are so grumpy all the time.)

If you want to test the light level of the room you’re in right now, you can download an app on your phone and measure it! I have no specific recommendation but this one works for iPhones. It will vary throughout your room, but you can try pointing it at the floor for a somewhat balanced reading.

I find it surprising that we are so okay with our indoor rooms being dark, relative to the outdoors. I suspect it’s a side-effect of how expensive light has been, historically. We’ve just always accepted a dim indoors as normal.

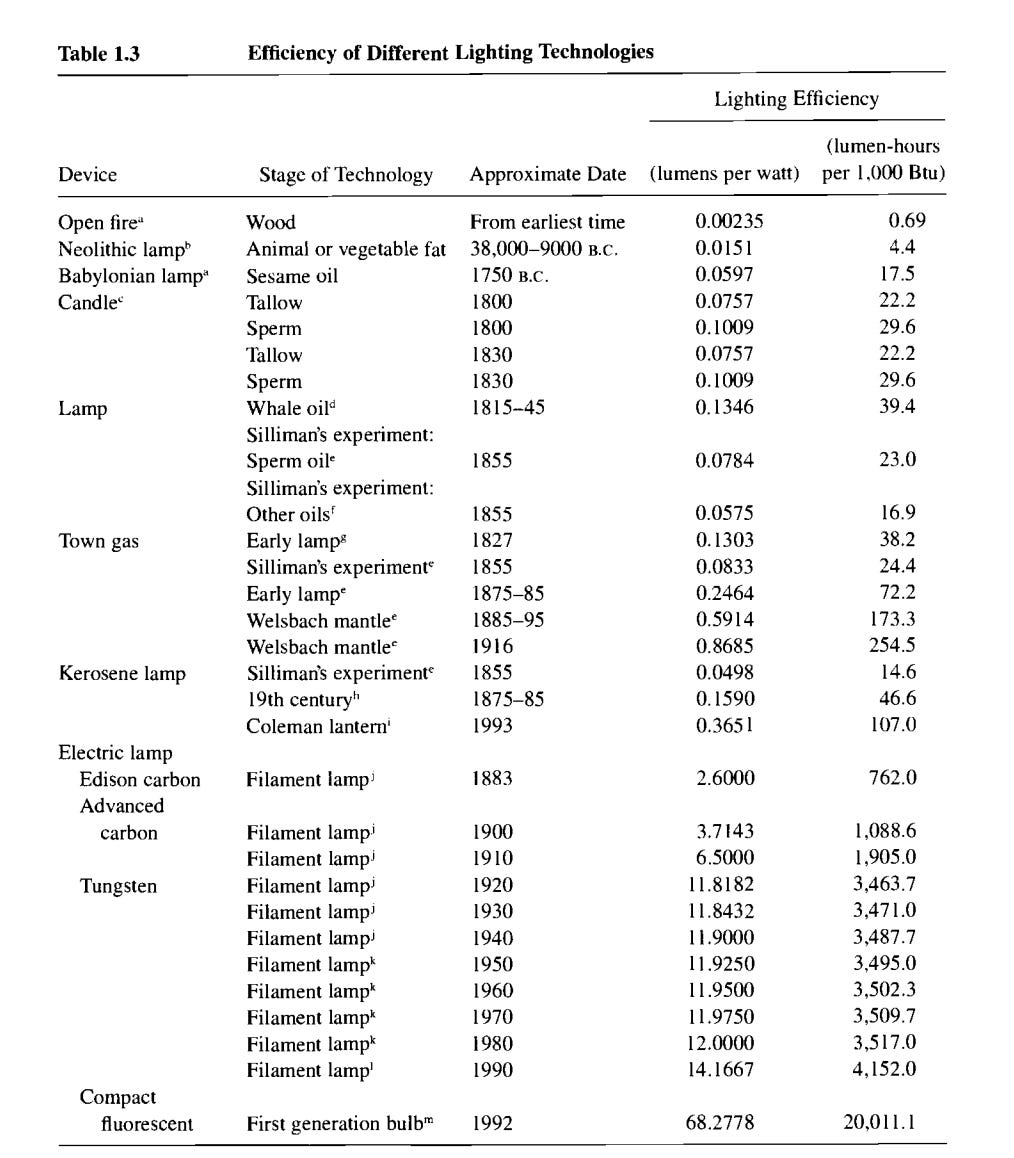

This famous 1994 paper was one of the first to collect data on how efficiently we humans have been able to make light, over time. Note the exponential increase over time! We got 5 times better at making filament lights from 1900 to 1990. And fluorescent lights are 5 times better than even the best filament lights in 1990!

Do you know what else is better than filament lights, and isn't represented here? LED lights. LEDs were a nascent technology in 1994. Since then we’ve learned to make LEDs that are 7-8 times more efficient than incandescent filament lamps.

More importantly, we’ve also learned to make high-quality LED lights. If fluorescent lights were so efficient in the 90’s, why didn't we use them more? I think we did, actually, but primarily in offices and hospitals – and what do you think of when you think of those environments? I think of horrible, sickly, overly-bright industrial settings. In the 90’s, we only had an awful light trade-off available to us: bright and awful fluorescent lights, or comfortable but dim incandescent light. (More technically, this is because fluorescent lights have terrible CRI. If you don't know what this means, I'll discuss in more detail later.)

30 years on, however, we can have both!

I’m not quite sure why it isn’t more widespread, but there’s nothing to stop you from installing high-quality, bright LED lighting in your home or office today.

How much light is enough?

I am going to claim that you don’t actually want your room to be as bright as the outdoors. Or, more accurately, you only sort of want it to be as bright.

You can see from the chart above that ‘outdoors’ varies a lot. Overcast days, at 1000 lux, for me, are a little too dim. I personally find straight daylight (10k-100k lux) to be far too bright; when I’m outside in those settings, I reach for a hat and sunglasses.

I’ve found that I prefer to aim for about 3000 lux. You probably also pick a light level you want between 1,000 and 10,000 lux. Remember that your perception of light is logarithmic, so these are the numbers that correspond to what you would perceive as linear:

1,000 1,600 2,500 4,000 6,300 10,000

Going higher seems like nice optionality, but you start to hit some practical limitations around power and safety. This is another reason why I’ve found 2-3,000 lux to be the sweet spot.

Once you’ve picked a desired lux, you can use the calculator below to figure out roughly how many lightbulbs you’ll need. You’ll also need the dimensions of the room you’re trying to brighten. I’ve loaded it with default values for smart 800 lumen bulbs I prefer (I’ll go into the details on why later), but you can change those too if you like:

Room Lighting Calculator

Room Width (ft): Room Depth (ft): Desired Lumens/m²: Lumens per Bulb: Bulb Wattage: Bulb Price ($): Cost per kWh ($): Calculate

(If you're seeing this through your email, the calculator won't show up for you. Click here instead.)

The calculations it does for you are:

Room width * depth to figure out how many square feet/meters we are covering

This isn't a completely fair calculation, because room height also matters – the lux produced by your light will depend on how much distance it has to travel to get to you. For our purposes I'm assuming your room is a standard 8-10ft high. I haven't thought too much about it, but if it's double-height I would suggest you double all the numbers above.

Square meters * lux to figure out how many lumens we need

Lumens / lumens per bulb to figure out how many bulbs you need

Various other multiplications and divisions of the bulb numbers to determine total cost and power usage.

The other values I’ll explain in depth later, but roughly speaking wattage determines how you need to arrange the bulb(s) for safety and power reasons and kWh tells you how much extra electricity you’ll use per month with this setup.

You might notice these aren’t exact. I’ve tried to round numbers where possible for simplicity.

Which bulbs?

The short answer is, Wyze White bulbs ($9 each). They have high (enough) CRI, are tunable and are affordable. If you have infinite money, buy Phillips Hue bulbs instead ($40); they’re pricey, but the Phillips smart system is by far the easiest one to set up. But if that makes sense for you, financially, you may want to look around for a better option.

Below I’ll go into why I prefer them.

What is light quality?

If you’ve made it this far, you probably (like me) are excited to learn that we’ve also learned how to assign numbers to light quality.

There are actually all sorts of numbers, and you can easily find all sorts of details about them on the internet. For our purposes, though, we only care about CRI; it’s usually one of the easiest metrics to find about a bulb. CRI stands for Color Rendering Index, and it’s important to get a bulb that is at least passable in CRI instead of terrible.

(You can go down a rabbit hole learning how to maximize CRI and R9 and other measurements, but I think marginal effort applied there is less useful than effort applied to placement and color temperature and the other factors I’ll write about here.)

Here are two panels representing the same color swatch, photographed under different light. The top/left panel shows it under 100 CRI, and the bottom/right panel shows it under 24 CRI. Note the huge difference in color! The 24 CRI colors are completely washed out and/or pink.

24 is about the CRI of a street light; in reality you’ll almost never interact with consumer light at that level. However, it’s common for cheap LED bulbs to be 60, 70 or 80 CRI. This is usually marked on the box, or on the ‘specifications’ section of the online shopping page. Fluorescent lights are usually 50-80 CRI, though there are apparently some high-quality fluorescent lights now. (Fluorescent lights also sometimes have other color problems, which makes for beautiful night-time cyberpunk photography but are less good for lighting your office.)

The best LED bulbs nowadays are 95-98 CRI. (Incandescent light is 100 CRI.) From trial and error though, I’ve usually found 90 to be sufficient. Reddit is full of complaints about how CRI can easily be 'gamed', which is maybe why the super-high CRI bulbs don't always lead to a much better experience.

That was a lot of numbers, so here is this information again in table format:

Light type CRI Street light 24 Fluorescent light 50-80 Cheap LED 60-89 Wyze White bulbs 90+ Expensive LED 95-98 Incandescent bulbs 100

If you don’t want to buy smart bulbs for whatever reason, the best LED bulbs usually come from American brands like Cree and Feit. (Some random trivia I’ve learned about LEDs is that they’re very advanced technology, so manufacturers are usually located in Japan, America and Western Europe.)

Why smart bulbs?

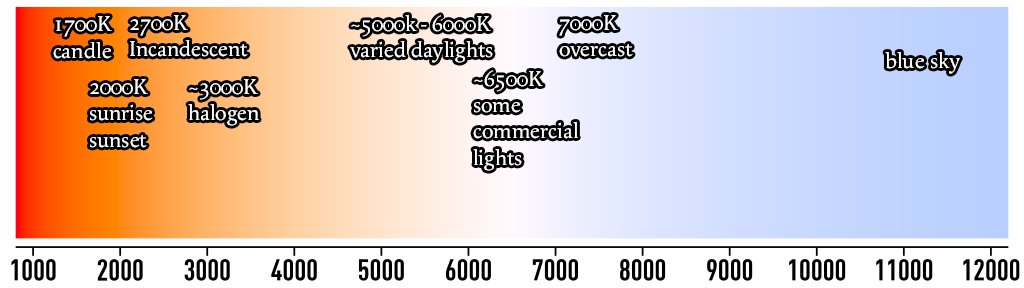

This one took me a long, long time to figure out, even though it’s intuitive once you figure it out. You want smart bulbs because the ideal light experience changes a lot throughout the day.

A fact that you may already know is that white light comes in different colors, from cool to warm. The diagram above shows the different colors and how they correspond to lights you’re familiar with. Most of the light we see during the day is cool (5000K+), and most of the light we see at night is warm (2700K+).

This presents a problem: what color of lights should you get?

Naively, you may expect 5000K to be the answer. Unfortunately, I find 5000K extremely painful and unpleasant to look at at night.

Is it better to get a warm light then? No; it ends up feeling very strange and unnatural during the day, even if my lights are very bright.

I tried splitting it down the middle and using lights that are 3000K, but that still had the strange daytime effect, and they were also far too cold at night.

Eventually I realized that I wanted my lights to be extremely bright and 5000K during the day, and to dim (slightly) and change color temperature with the sun as it set. This is why I recommend using smart bulbs; they can do this automatically!

Note: The home automation systems can be finicky to set up. If you already hate them, you can instead set up *two* ‘dumb’ light sources attached to separate smart dimmers: one with 5000K lights and one with 2700K lights. Set the 5000K ones to be on during the day and dim around sunset, and have the 2700K lights turn on at night. If you choose this path, make sure the bulbs you buy still have high CRIs.

Placement

Let’s take a brief break, and look at this Vermeer painting together.

Obviously, this room is far too dark. It’s a great place to develop long-term eye problems. But the amount and shade of light filtering in through the window and softly illuminating the young woman is stunningly beautiful. This painting is a masterpiece for many reasons, but one of them is because of its portrayal of light.

Amateur photographers quickly learn that the best portraits are taken on overcast days, or of subjects sitting by a window. It’s because this light is diffuse and soft.

If there’s one lesson here it's that using high-quality light matters a lot, but where it’s placed and how it’s diffused also matters a lot to your experience of it. You won’t be able to make all the parts of your study as beautiful as this Vermeer, but it’s worth keeping it in mind while you decide how you want to place your bulbs.

A whirlwind tour of the rationalist lighting ecosystem

Back to business. So you plugged in your information into the calculator above, and you’ve discovered that you need 24000 lumens. Using the Wyze bulbs I suggested means you need 30 bulbs.

“But I don’t have 30 sockets in my room to plug lights into,” you say. “What am I supposed to do?”

Never fear! Much ink has been spilled discussing lights on the rationalist blogosphere. Unfortunately for me, I only realized this after I started writing this article. If I’d known, I probably would have picked a different topic to write about.

At a high level, though, many people are trying to solve the same problem: making rented home offices nicer to work in. I’ve seen roughly 3 approaches to this:

DIY single-point sources

Lumenators

Custom LED panel setups

Spoiler alert: I prefer lumenators myself, but I’ll go through the pros and cons of each of them.

DIY single-point sources

Ben Kuhn is the person who got me into this whole lighting hobby. About five years ago he wrote Your room can be as bright as the outdoors, where he details how you can create a 30,000 lumen bulb using corn lights and/or bulb splitters. For a 10x10 sqft study this produces 3000 lux, which is great!

However, when I’ve tried this, various people around me have objected, citing reasons like “it hurts my eyes” and “ouch.” Maybe you will have better luck! I also have found that I personally don’t like it because I think single points of lights diffuse light poorly. This means some areas are far too bright and others are not nearly bright enough.

That said, there are situations where an approach of this form can make sense. I once set up extreme residential lighting in a place that already had 6 overhead fixtures installed, and I was able to place 4 1,600-lumen bulbs in each of them using a 4-way splitter, for a total of 30,000-40,000 lumens. (Unfortunately, those weren’t smart bulbs, and it’s hard to find smart bulbs above 800-lumens of brightness.) It can also serve as a stopgap, or a test, if you want to see if adding another 3,000-8,000 lumens of light to your workspace will make a difference.

You need to be very careful around wattage if you do this (see notes at the end on fire safety). How careful depends on how many bulbs you have and how powerful they are. When I’ve set up lights like these in the past I’ve used:

1x these IKEA shades. Hang them from your ceiling so they are not in eyeshot. The shades are large, which is good because they will diffuse light and make it less painful to look at.

4x these Cree bulbs. (18w each for 2000 lumens. Multiplied by 4 it is 72w. These are not smart bulbs; I can’t find affordable 2000 lumen smart bulbs. You could also use the Wyze bulbs above, though then your light will only be 3200 lumens.)

1x this 100w ceiling socket cord.

Alternatively, here is a very bright light product someone has made and is taking pre-orders for. This also suffers from the ‘poor distribution of light’ problem, but I am impressed with the founder for trying at all!

Lumenators

My preferred approach is something known as a ‘lumenator’. Basically, this is a string of lights placed up on the ceiling, with bulbs installed in them. The link above provides a guide on how to make them, though I disagree with some of their choices!

My setup has two parts:

48 ft, 24-socket Commercial Grade String Light Cord (medium/E26 base) (https://partylights.com/48-Medium-Base-Stringer-Black/, rated for 960W).

24 Wyze bulbs (8 watts each, for 192W total)

Hooks for hanging (finicky Command hooks if you don’t want to damage your walls, screw-in ones if you are ok with spackling)

You can also use these 10-socket lights if you want fewer bulbs.

Using the right light cord is important and easy to get wrong. It must match the base of your cords (E26, for Wyze bulbs, also the most common one), and have a power rating appropriate for the bulbs (these can handle 11-15W per socket; some light strands sold on Home Depot can only take 1W since they are decorative).

Bizarrely, there seems to be only one design manufactured anywhere for this type of fixture. I checked Taobao to see if I could find a different generic Chinese version, or one with less space between the sockets, and failed. If you need more than 24 bulbs, you should get two; you can plug them into each other, up to the wattage limits specified.

The Wyze bulbs already are covered by a diffuser which does enough, and they aren’t individually that bright anyway, so I don’t think you need the lantern covers suggested in the Less Wrong post.

Note: You may need to use a knife to cut off the ‘weather-resistant sockets’ to get your bulbs in. I didn’t need to for the Wyze bulbs but I did for some cheaper Amazon bulbs I previously tried.

Panels?

Lincoln Quirk suggests that maybe the thing we really want is ‘fake windows.’ I haven’t tried it. It seems like a neat idea in theory, but it requires electrical knowledge beyond what I know about LEDs.

There’s definitely a space here for someone to create a custom LED panel. It would be neat. Then you wouldn’t have to do all this futzing around with the bulbs and the light strands and calculators. I once thought about trying to design and sell this, and then I decided that I wasn’t insane enough to start a hardware business.

Miscellaneous

One day I went around and hung pictures on all our walls. The general guidance is to hang pictures roughly so that they are at eye height. That night my partner said, “It’s very nice that you hung up all the paintings. But why are they so strangely low?”

“There’s nothing wrong with them!” I responded. “😠!”

Note that I am 5’3” (159cm) and my partner is 5’11 (179cm). This is largely intended as a reminder that what is above eye level for you might not be above eye level for everyone; and having a bright light source at eye level is extremely unpleasant.

For this reason I recommend putting your light as high up as possible. Hang it from the ceiling, if possible. If you must affix it to the wall, put it as close to the ceiling as possible. In the past I have put it behind wherever it is I’m working, so that I can keep it out of eyeshot. You’ll need to buy, borrow or steal a ladder to do this well.

tl;dr

This is too complicated. Just tell me what to buy.

Use the calculator to figure out roughly how many bulbs you need. Then buy Wyze White bulbs, command hooks and one of these for each 10 bulbs you need. For maximum effect, you will need to figure out how to control the Wyze bulbs using the app, which will be slightly annoying. You’ll also need a ladder.

I am a Serious Adult and I want a less janky setup. What should I do?

You mean you don’t want your house to have the aesthetic of a Berkeley group house? What a fascinating preference.

Honestly, I would recommend taking the lumenator or single-source approach first anyway; it’ll cost you $100-500, which is small potatoes compared to doing a proper renovation. It'll also help you figure out where and how you want your light to be. Just accept the snarky comments from your friends for a month. They might be too busy enjoying your well-lit room to notice anyway.

I have tried to figure out what the Actual Solution is here, and mostly failed. However I know it can be done, as I once worked in an office space that had solved this lighting problem beautifully.

A solution I commonly see in Asia — where I generally find the indoors to be much better lit — is recessed overhead lights. This is nice because then you can install very bright lights but not have them in your eyes, and the light comes out of the right place in the ceiling. Presumably you need to contract with a builder to get the right LED panels and controls for them.

I live in Europe/Asia/a part of the world that is not North America. What should I do?

Enjoy your urban, walkable environment and sunny apartments!

I apologize for the America-centrism. It’s the only place I’ve tried most of these approaches, so it’s the only place I can provide details. Most of it should apply, though you’ll need to find local sources for parts. The main thing to note is that the standard power requirements may vary, because you’re wired for 220V and not 110V.

Health and Safety

Will this cause a fire/blow a fuse?

I don’t think so. (This is to the best of my belief! I am not an electrician.)

Most consumer lightbulb sellers tell you all the numbers you need to know. Importantly, the wattage tells you most of what you need to know. If you stay under the wattage ratings suggested by your

Do be careful with your extension cords. The US is unique among developed nations in allowing consumers to purchase unfused extension cords with very low current ratings, aka extremely dangerous fire hazards. Try to buy fused extension cords, or try to plug your fixtures directly into the wall.

One risk you might be worried about is blowing the fuses in your wall. But your average household circuit can conservatively handle about 15A at 125V (assuming you’re in the US). If you multiply those together to get the wattage, and we see that it can handle about 1,875W of power. Your microwave, by comparison, draws approximately 1000W of power when it is on. So if you can run a microwave on it, you’ll be fine.

If you want to go crazy and output 10k lux — or if your room is particularly large, and you only have one circuit — you will start to run into problems. But it turns out that LEDs are just so efficient, and our home circuits designed for inefficient incandescent bulbs, that you are effectively now using your home almost exactly in the way it was designed for. If you have concern, consult an electrician.

How much will this cost me in electricity?

A fun fact about North America is that electricity prices vary wildly across the continent. In the Canadian east, which imports most of its power from Quebec’s abundant hydropower, electricity can be 5-10c per kWh. In California, a state that famously doesn’t believe in capitalism, it can run to about 40c per kWh (I kid you not).

Your 100W light, if you make very odd choices and keep it on all day, will draw 100W * 24h = 2.4kWh per day. (A kWh is a kilo-Watt hour, used to measure the use of electricity over time. It represents the continuous draw of a thousand Watts over an hour). Assuming there’s about 30 days in a month, this will cost you about 72kWh, or about $8 to $36, depending on where you live. In practice, I’m guessing you would only keep it on half the day, so you can cut that number in half.

This is expensive, but consider that it trades off against the cost of therapy and being sad. Given that I think it’s well worth it, but you can make your own choices. Both of these numbers are produced by the calculator above.

Thanks to Ben E and Ross R for feedback on an early draft! Special thanks to Ben Kuhn for careful proofreading and substantive feedback.